A Brief History of Lipulekh Deals: India and China Agree, Nepal Protests

On 29 April 1954,

India and China signed an “Agreement …on Trade and Intercourse with the Tibet Region of China and India” in Beijing. The first sentence of Article 4 of the agreement states:

“Traders and Pilgrims of both countries may travel by the following passes and route : (1) Shipki La pass, (2) Mana pass, (3) Niti pass, (4) Kungri Bingri pass, (5) Darma pass and (6) Lipu Lekh pass.”

We could not find any evidence of Nepal reacting to this Indo-China agreement. The 1950s was one of the most unstable periods in Nepal’s recent history. Political instability followed with the end of an oppressive Rana regime in 1951. India had become independent seven years earlier and enjoyed “close to total political and economic domination” in Nepal. Likewise, it was also the time when Indo-China relations were at their best as reflected in the Hindi slogan Hindi Chini Bhai Bhai (Indian Chinese Brothers). The agreement probably was a part of the Chinese ‘thank you’ to India for being the first non-communist country to recognize the Maoist takeover of Beijing in 1950.

“Nepal is hurt with China’s move because it has always supported and respected China’s geopolitical integrity.

Sudheer Sharma, Nepal magazine, 14 May 2005.

Sino-Indian ties deteriorated following a war between the two in 1962. Their ties started to normalize only in the 1990s with the Indian decision in 1988 to abandon its policy of settling “territorial issue” for “normalization of relations.”

On 13 December 1991,

India and China signed a memorandum on the “Resumption of Border Trade” between Uttar Pradesh and Tibet Autonomous Region by establishing “border trade markets” at Gunji (in Kalapani/Lipulek area) and Pulan. The fourth point of the agreement states: “Intending to facilitate the visits of persons engaged in border trade and the exchange of commodities and means of transportation, [India and China] have decided that Lipulekh (Qiangla) be the border pass for the entrance and exit of the said persons, commodities and means of transportation from the two sides.”

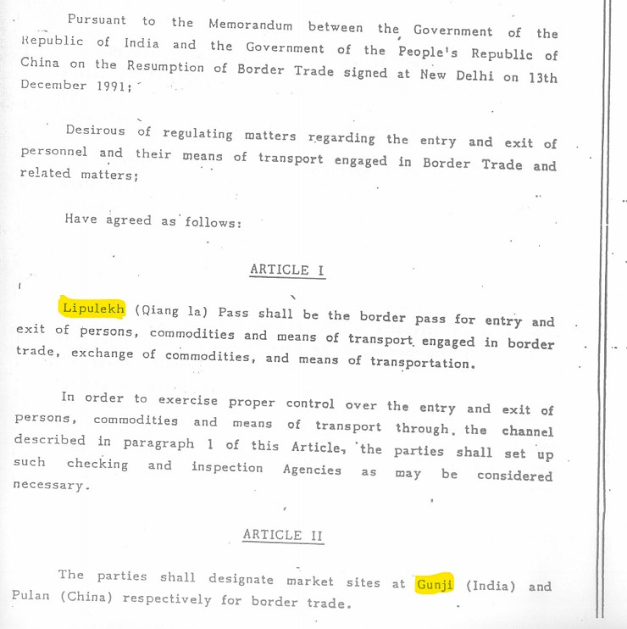

On 1 July 1992,

India and China signed a protocol on “Entry and Exit Procedures for Border Trade… according to the memorandum” of 1991. Article 1 states:

“Lipulekh (Qing la) Pass shall be the border pass for entry and exit of persons, commodities, and means of transport engaged in border trade, exchange of commodities, and means of transportation.

To exercise proper control over the entry and exit of persons, commodities, and means of transport through the channel described in paragraph 1 of this Article, the parties shall set up such checking and inspection Agencies as may be considered necessary.”

This time too, Nepal was going through another round of instability. The country had just regained democracy in April 1990 with partial support from India. A new government had just been elected in May 1991 and India’s ability to influence Nepali politics was once again very high. (The Indians were celebrating their success in punishing king Birendra who had reached out to China to buy arms. It was another instance when China chose to appease India at the cost of Nepal’s interests.)

On 11 April 2005,

during Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao’s India visit, the two countries signed a protocol “on Modalities for the Implementation of Confidence Building Measures in the Military Field Along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas”.

Clause 2 of Article 5 of the agreement states: “Both sides agree in principle to expand the mechanism of border meeting points to include Kibithu-Damai in the Eastern Sector and Lipulekh Pass/Qiang La in the Middle Sector. The precise locations of these border meeting points will be decided through mutual consultations.”

Nepal’s Foreign Ministry issued a statement on 10 May 2005 in which it stated that Nepal had asked China about the issue and the Chinese Government, through the Chinese Embassy in Kathmandu, had clarified to it that the agreement had nothing to do with Kalapani, according to a report in Nepal magazine.

It was perhaps the first time Nepal had objected to the Sino-Indian agreement on Lipulek. But the situation, once again, was not favorable to Nepal.

King Gyanendra had executed a coup d’etat two months before the agreement. Just like his father Mahendra in the 1960s who reportedly shut down his minister who mentioned to him of Indian encroachment in Kalapani, Gyanendra too was perhaps not inclined to strongly articulate Nepal’s objection. Similar to Mahendra, he must have feared that raising the issue would further antagonize the Indians who were already disappointed with him for dismissing an elected government (as they were with Mahendra for the same reason).

However, the Nepali press reacted to the agreement and criticized China in particular for disregarding Nepali sentiment. Writing in the Nepal magazine and Kantipur daily, editor Sudheer Sharma said:

“Nepal is hurt by China’s move because it has always supported and respected China’s geopolitical integrity. Nepal has always backed China as is apparent from its closing down of Dalai Lama’s Nepal office and has supported the Chinese position on Taiwan. Nepal should have benefitted from the improvement in relations between her two powerful neighbors but it seems to have been punished. But while such serious events are taking place, the government is mute. We really have to wonder what the so-called nationalistic government representatives are doing about this issue.”

Another commentary, on UWB, also criticized China. “The biggest irony is that when our royal and ‘nationalistic’ government was busy issuing countless press releases affirming its support toward One China Policy and stressing that Taiwan was an integral part of China, our northern neighbor was giving a thumbs-up to the Indian encroachment of Kalapani,” it said. “After seeing all this, I wonder why are we still adopting the One China policy. Why are we closing down the offices of Tibetan refugees in Kathmandu? Why are we issuing statements supporting China’s anti-secession law targeted at the national sovereignty of Taiwan?”

On 18 September 2014,

India and China signed several documents during the State Visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping to India. Number one on the list, as published on the website of the Indian Foreign Ministry is a memorandum of understanding “on Opening a New Route for Indian Pilgrimage (Kailash Mansarovar Yatra) to the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China”. The Indian Foreign Ministry states that “the MoU provides for conducting the annual Kailash Manasarovar Yatra through Nathula Pass in Sikkim [in] addition to the existing Lipulekh Pass in Uttarakhand.”

On 15 May 2015,

China and India issued a joint statement during Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to China. Point no. 28, under the section ‘Trans-border Cooperation’, states that the “two sides agreed to hold negotiation on augmenting the list of traded commodities, and expand border trade at Nathu La, Qiangla/Lipu-Lekh Pass, and Shipki La.”

Nepal’s objection to the 2015 agreement was stronger. The Nepali public, including opposition parties, protested. Parliament’s International Relations and Labour Committee summoned Foreign Minister Mahendra Bahadur Pande on 9 June 2015 to interrogate him on Nepal’s position on the issue and “criticized the government for failing to strongly counter the Sino-Indian agreement”. Pande told the Committee that the government had already drawn the attention of India and China on the issue of Lipulek and that the result was “expected within days”. According to a Nepal magazine report, Pande said, “Details of the diplomatic efforts could not be disclosed immediately.”

According to Nepali Congress leader Prakash Sharan Mahat who became Foreign Minister in 2016, Prime Minister Sushil Koirala “himself called up Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi [in 2015] to express Nepal’s displeasure over the Indian-Chinese agreement on Lipulek.”

On 9 May 2020, Nepal’s Foreign Ministry disclosed what it had done in 2015:

It may be recalled that the Government of Nepal had expressed its disagreement in 2015 through separate diplomatic notes addressed to the governments of both India and China when the two sides agreed to include Lipulek Pass as a bilateral trade route without Nepal’s consent in the Joint Statement issued on 15 May 2015 during the official visit of the Prime Minister of India to China.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Singh Durbar, Kathmandu, 9 May 2020.

It is evident that Nepal has only in recent years started to strongly articulate its objection to the Indo-China agreement on Lipulek. The strongest reaction to date came on 20 May 2020 when Nepal included Lipulek and Limpiyadhura in its new map. There are several reasons behind Nepal’s hardened stance on Lipulek including Nepal’s domestic politics and the fluctuating level of Indian influence in the country.

Analyzing Nepal’s cartographic assertion in 2020, the country has never been in a better position to deal with India. There is only one power center, the Nepal Communist Party, which holds a supermajority in parliament. The public has always been mostly critical of India’s hegemonic behavior and they are solidly behind the Government on national sovereignty and integrity. The opposition parties, particularly the Nepali Congress, agrees with the government’s decision to release the map. More than anything else, there is no active insurgency or a political movement against the government or the state of Nepal as was the case in the three decades preceding the restoration of democracy in 1990, or the late 1990s, early noughties, and the years before the promulgation of the constitution in 2015.

“Following Nepal’s protest note on Lipulek, China became alert to Nepali sensitivities and stopped all activity there. China will maintain status quo and is waiting for Nepal-India to resolve the matter.”

Leela Mani Paudyal, former Nepali ambassador to China, May 2020.

Nepal’s stronger stance against Sino-Indian agreements on Lipulek might have finally had an impact. Nepal’s former ambassador to China, Leela Mani Paudyal who was recalled by the Oli administration two months ago, has told Kantipur last week that “following Nepal’s protest note on Lipulek, China became alert to Nepali sensitivities and stopped all activity there. China will maintain the status quo and is waiting for Nepal-India to resolve the matter.”

No comments